©

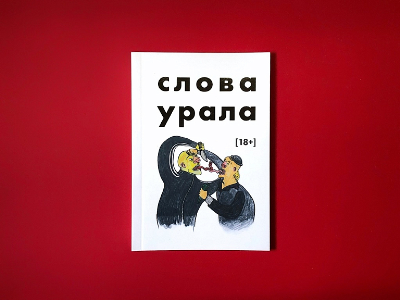

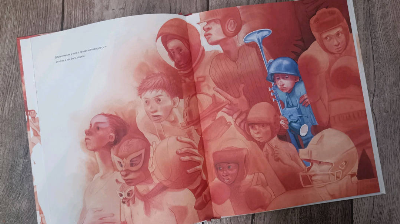

Фраза «Гнити — значить жити в межах РФ. Де народився — там і згнив» колись звучала як саркастичне народне прислів’я. Тепер — це вже привід для скарг до поліції. Вислів походить зі збірки «Слова Урала», яку ще 2018 року уклали двоє митців-аматорів. Книжка починалася з 150 слів і виразів, зібраних з побутового мовлення місцевих мешканців. Згодом до авторів почали надходити листи з новими фольклорними тлумаченнями і за словами зберегли право бути «гострими», сумними, але справжніми. Видання марковане грифом «18+», продається у герметичній упаковці й подається як гумористичне зібрання, яке не претендує на об’єктивність. Проте сьогодні воно стало черговим подразником для представників російської влади. Депутати Держдуми вважають, що книжка може «деморалізувати молодь» — адже, як кажуть вони, гнилим може бути лише Захід, а не росія. Цензура стосується не лише фольклору. У російських книгарнях також посилюється кампанія проти дитячих перекладених книжок. На думку парламентарів, такі тексти «пропагують деструктивну ідеологію» — не героїзують хлопців, заохочують дівчат до самостійності, критикують традиційні ролі. Під пильне око цензорів потрапила зокрема «Дівчинка-сонечко» Девіси Джекі (США) — історія про внутрішній світ дівчинки, що намагається бути собою. Ще один приклад — «Солдатик» Крістіни Белемо (Італія), де головний герой, маленький олов’яний солдатик, раптово перестає думати про війну, коли опиняється у теплому домі. Саме цю зміну внутрішнього фокусу депутатка Думи назвала «неприпустимою»: мовляв, солдатів не можна зображати «знаряддями безглуздих убивств» — тільки як захисників батьківщини. Мінкульт росії хочуть зобов’зати контролювати не лише зміст, а й ідеологічне навантаження дитячих видань. Ба більше, видавці можуть отримати юридичну відповідальність за «деструктивний контент» — аналогічну до відповідальності інтернет-платформ. Поки фольклористи збирають живе слово і записують культуру «знизу», згори їм пропонують тишу. Але слова — живуть. І поки живуть — не гниють

Ural Folklore Becomes a Threat to Russian Authorities

The phrase “To rot means to live within the borders of the Russian Federation. Where you're born is where you rot” once echoed as a biting folk saying. Today, it is a potential cause for police investigation. The expression originates from the collection “Words of the Urals”, compiled back in 2018 by two amateur artists. The book began with just 150 colloquial expressions gathered from the everyday language of locals. Over time, letters with new phrases and folk interpretations started pouring in — giving these words the right to be sharp, sorrowful, but real. The publication is marked 18+, sold sealed, and explicitly positioned as a humorous collection without claims to objectivity. Still, it has now provoked outrage among Russian lawmakers. Members of the State Duma claim the book may "demoralize youth" — because, in their words, only the West can be considered "rotten," never Russia. Censorship, however, doesn't stop at folklore. A wider campaign is gaining momentum in Russian bookstores against translated children's literature. According to some parliamentarians, such works “promote destructive ideology” — failing to glorify boys as heroes, encouraging girls toward independence, and undermining traditional gender roles. One particular target of criticism is “Ladybug Girl” by American author Devessa Jackie — a story exploring the inner life of a girl learning to be herself. Another is “Little Soldier” by Italian writer Cristina Bellemo, in which a small tin soldier suddenly stops thinking about war when he finds himself in a warm house. This shift in perspective was deemed “unacceptable” by one Duma deputy, who argued that soldiers must never be portrayed as “meaningless instruments of killing,” but only as defenders of the motherland. Russia’s Ministry of Culture is now being urged to oversee not just the content but also the ideological orientation of children’s books. Moreover, publishers may soon face legal liability for so-called “destructive content” — similar to the accountability of digital platforms. While folklorists continue to collect the living language and document grassroots culture, they are increasingly being met with silence from above. But words — they live on. And as long as they live, they do not rot.

©

1435